The formation and evolution of entrepreneurs and their enterprises are best exemplified in the stories of the three entrepreneurs in Asia. As to why they were picked out among the myriad of famous entrepreneurs is Dr. Morato's way of explaining the age-old debate of whether entrepreneurs are born or made. These three are Lim Bee Huat, Jay Bernardo and Iwan Tirta.

The stories of these three show the different paths that led them to be successful entrepreneurs. As each story unfolds, one would realize that indeed, some entrepreneurs are born as one while others are also nurtured to become one eventually. In the same way, their stories become inspirational as the student reads through them because their stories are relatable. One thing in common though, these entrepreneurs share the same passion for what they do and the strength of character and perseverance that they held on to as they try to reach the top of their respective entrepreneurial careers. There were signs that all three were born entrepreneurs because they have characteristics that set them apart from the others. They were also non-conformists, have independent minds and masters of their own fates. While they may be born as entrepreneurs, they were also nurtured and became products of their own environment.

One thing in common though, these entrepreneurs share the same passion for what they do and the strength of character and perseverance

Jumping off from the three stories are the different sources of innovation and creativity. These sources include: talent, adoption and adaptation, and think bigger, bolder & better. Each source is enriched with the examples from the three entrepreneurs. The first source of innovation and creativity is talent which comes in many forms. Lim Bee Huat has an imaginative mind. Jay Bernardo is innately intelligent. Iwan Tirta’s talent is his creative mind, a whole brain thinker. The second source comes in the form of adoption and adaptation of prevailing business practices, processes or technologies. In the case of the three entrepreneurs, they went beyond these existing ways of adapting and innovating. Thirdly, these three entrepreneurs are all visionaries. They dreamt, they aspired and they persevered their way to achieving their goals.

It also discusses the three persons of the complete entrepreneur – Originator, Operator and Organizer. This means that an entrepreneur can be made up of at least one or a combination of or all of the “persons” of the complete entrepreneur. Hence, it is difficult to be a complete entrepreneur. Often, the attributes of the complete entrepreneur are found in two or more persons running the entrepreneurial organization. It likewise discusses the difference between entrepreneurial leaders and businessmen/ managers of which there are seven differences enumerated.

Towards the end, there is also a discussion on the formation of entrepreneurial leaders and the challenge posed to leader formators that include educators and entrepreneur themselves who want to mentor or mold their people.

Social enterprises strive to attain a good balance in the pursuit of their three bottom lines: the PESO bottom line (enterprise viability), the PEOPLE bottom line (social impact) and the PLANET bottom line (environmental conscientiousness). The three PESO or enterprise viability metrics are Financial Returns, Market Returns and Economic Returns. The three PEOPLE or social impact metrics pertain to three groups: the social enterprise beneficiaries; the social enterprise customers and the social enterprise employees. The three PLANET metrics also revolve around: (1) Monitoring and evaluating the environmental impact of the social enterprise through the quality levels of major environmental indicators which the social enterprise might affect; (2) Assessing the negative consequences on the environment that the social enterprise might cause to be less sustainable; and (3) Accounting for how much the social enterprise has contributed to enhance and improve the productivity and long-term sustainability of the natural resources.

Technology, social, and market innovations are the three critical areas of innovation that most beguile entrepreneurs. Technology innovation refers to both the physical and tangible form of technology as well as the intangible systems and processes of making new products or rendering services. Social innovation pertains to how people are mobilized, organized, motivated, capacitated, energized, networked and empowered to undertake a common effort for a common cause that would maximize the benefits or end results desired for collaborating stakeholders. Social innovation is about social engineering that involves social architecture (people STRUCTURES), social behavioral science (people SYSTEMS) and social economics (SHARED RESOURCES). Market Innovation entails the introduction of new or substantially improved products and services to consumers who offer good revenue-generating prospects.

Beneficiaries of Subida, 2019 BPI Sinag Awardee

In summary, the social entrepreneur should employ a systematic process of assessing a technology to ensure that it has a fighting chance at becoming successfully adopted and applied. Furthermore, the social entrepreneur has the daunting task of mobilizing, organizing, capacitating, networking and empowering individuals, families and communities in order to find strength in solidarity, which was the most formidable and, often, most frustrating of them all. Market innovation, on the other hand, is not about tweaking and “refreshing” old products to look like new by introducing product features and attributes which really do not provide significantly more benefits to the consumers.

The best form of social enterprise is composed of worker-owners who may even be their own suppliers and markets because most, if not all, of the economic and social benefits emanating from the social enterprises accrue mainly to these workers-owners-suppliers-customers according to Dr. Eduardo A. Morato, Jr. (author).

The author cited two exemplary social entrepreneurs and their social enterprises: (1) Ruth Callanta, founder of the Center for Community Transformation (CCT) and (2) Sylvia Muñoz-Ordoñez, executive director of Kapampangan Development Foundation (KDF). The inspiring stories of these two social entrepreneurs and how they became the driving forces behind their respective organizations have been chronicled by the author. While CCT took on a very high-contact transformational approach to significantly change the way of life of the street dwellers, KDF took on the high-impact transactional approach in providing surgical and other medical services to PWDs.

It also discusses corporative and inclusive business. Corporative, a social enterprise hybrid, stemmed out of the pressure that began to force non-government organizations to be more “sustainable” as they sought additional sources of income aside from the grants and donations. They themselves ran separately or jointly income-generating activities with the communities. Inclusive businesses pertain to large businesses whose corporate social responsibility (CSR) were restricted to community relations programs and projects which emphasized dole outs to communities surrounding their factories, mining operations, power plants and the like.

It is likewise important to measure the impact of the social enterprise vis a vis their social purpose. The author cited his own experience in leading the transformation of Bayan EDGE from being a mere microfinance institution into a micro and small enterprise development institution. The discussion on environmental impact revolved around the story of Gina Lopez, founder of ABS-CBN Foundation and her national advocacy to heighten environmental awareness and protection and to provide viable alternatives to the destructive effects of mining, illegal fishing, wanton natural resource exploitation and highly-toxic food production using harmful chemicals.

It is likewise important to measure the impact of the social enterprise vis a vis their social purpose.

The author included a literature review on the evolution of the social economy and the role of social innovators. The discussion on the social economy revolved around cooperatives, mutual aid societies, associations and foundations. This was followed by a discussion about the need for appropriate technological innovation, effective social innovation, and a customer-focused market innovation. Furthermore, it discusses the daunting task of the social entrepreneur in trying to achieve a good strategic fit in converging the market’s expectations, the appropriateness of the technology, and the soundness of the social organizational design.

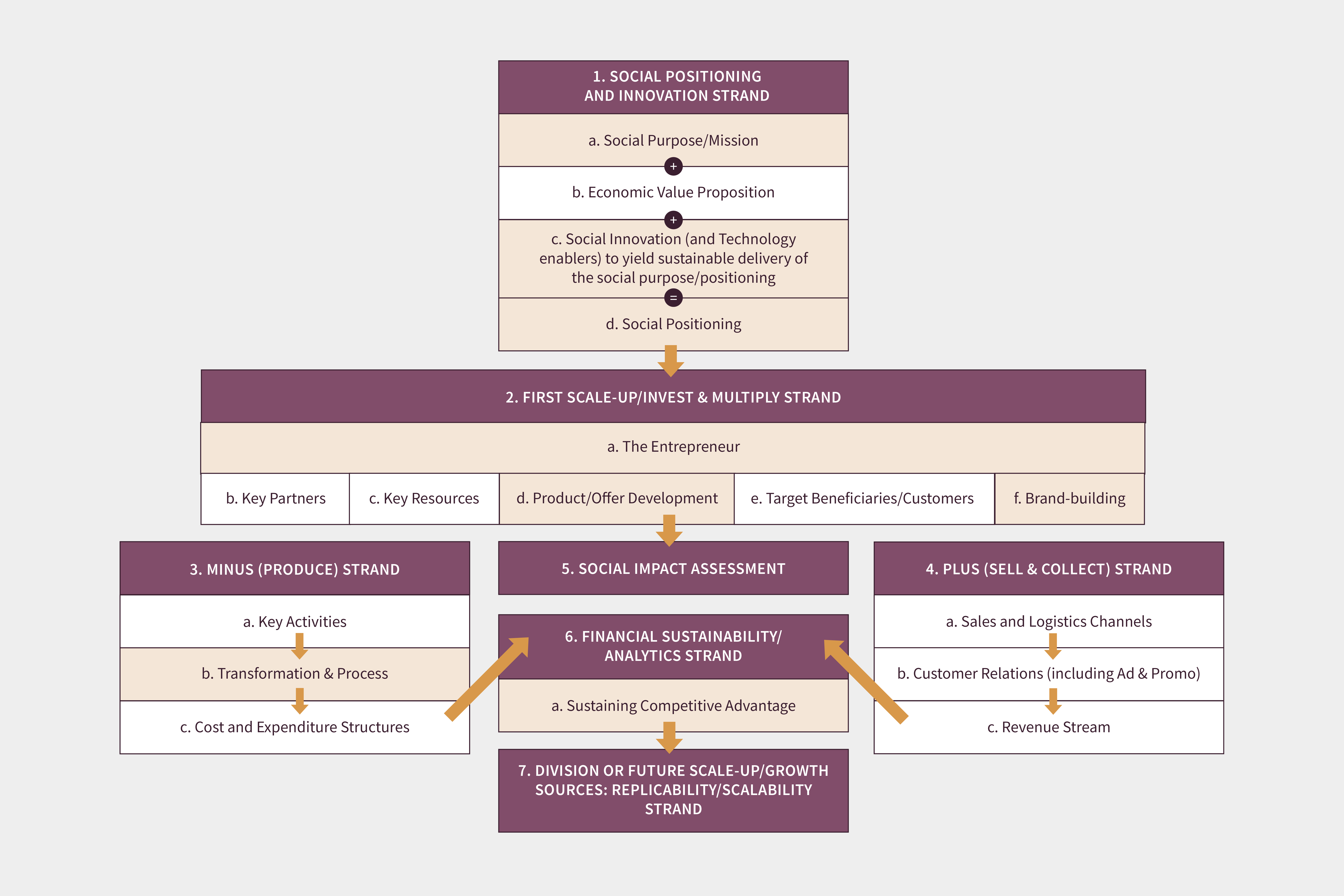

The Social Enterprise Model Tapestry is a tool that was designed to measure the progress of social enterprises which are the product of three social enterprise centered programs namely: BPI Sinag Accelerate, British Council CSO SEED, and the Quest for LOVE (Loving Organization for Village Economies). The tapestry was used as a tool in the mentoring of the winners of the mentioned programs from 2016 to 2017. It has undergone modifications and the third version has been determined appropriate for use in mentoring social enterprises. It remains a work in progress.

The Social Enterprise Model Tapestry is a modified version of Business Model Canvas which was introduced in 2008 by Alexander Osterwalder. The Tapestry contains nine additional blocks increasing the number of blocks to eighteen. The eighteen blocks are weaved into seven strands. These adjustments were made in order to contextualize it for social enterprises.

The seven strands are clustered in such a way that it illustrates the circular flow of the enterprise life.

Weaving, Beneficiary of AKABA, 2016 BPI Sinag Awardee

If you are interested in reading the full material, visit www.bayanacademy.org.